Regulations yes – but in moderation

A sense of proportion is needed when designing framework conditions for waste. If those involved in regulation overshoot the mark, they will prevent recycling and circularity. A current example of this is the LAGA Notice 23, or M23 for short. It is intended to ensure a uniform nationwide approach to the disposal of mineral construction and demolition waste, taking into account possible asbestos contamination.

Affected structures and waste types

“If introduced nationwide, M23 would affect all buildings whose construction began before 31 October 1993,” explains Christopher Kuhlmann, legal advisor to the REMEX Group. Until that date, asbestos-containing materials were used in German construction. After that, the sale and use of products to which asbestos had been artificially added was prohibited in Germany. “Buildings whose construction began after this date are therefore automatically considered asbestos-free.”

In most cases, asbestos is found in older buildings, e.g. in asbestos cement boards that were installed in roofs, facades or air shafts in the past. “This asbestos-containing waste can be separated through orderly demolition,” says Kuhlmann. The old edition of LAGA M23 from 2015 provided for such appropriate demolition measures and separate collection of asbestos-containing materials. “The remaining mineral waste fractions can usually be recycled without any problems and returned to the production cycle,” says Kuhllmann.

LAGA Notices

LAGA is the Federal-State Working Group on Waste, a group of employees from the state ministries responsible for waste and the Federal Ministry for the Environment. Notifications such as M23 have no direct legal effect; they are not binding on either public authorities or private individuals. State governments can recommend or prescribe their application to the according state authorities by means of decrees. Since the federal states can make their own interpretations in these decrees, the ‘nationwide’ introduction usually leads to a federal patchwork of regulations. Some federal states have already declared that they do not intend to implement M23. [1]

Unnecessary extension

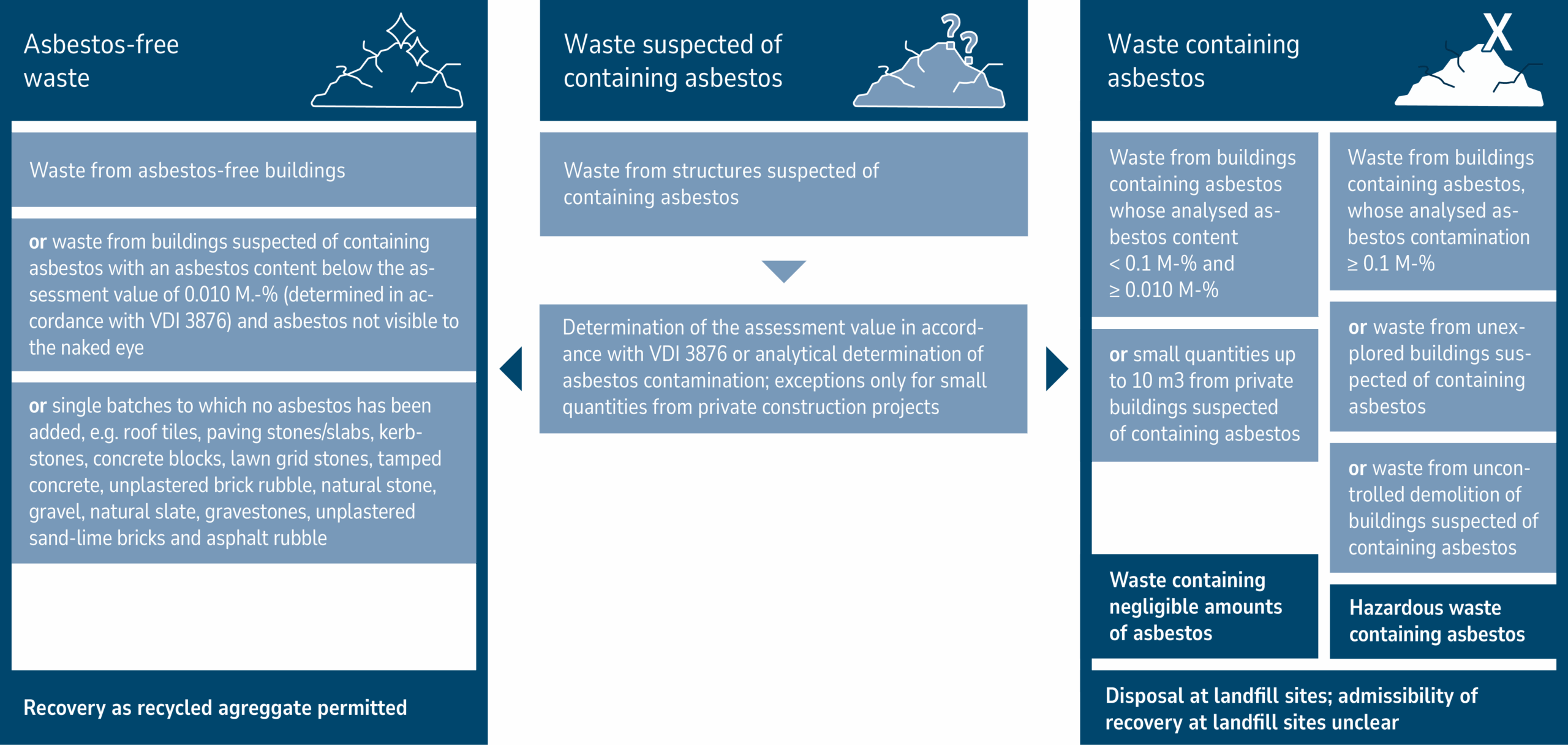

However, the updated M23 goes one step further – and, if applied consistently, would result in many types of waste that are in principle suitable for recycling being sent to landfill. The reason for this is that it no longer only covers waste containing asbestos, such as sprayed asbestos and asbestos fibre cement products from demolition and renovation work, but , due to its general extension to construction waste, also covers fillers, paint coatings and spacers for concrete reinforcement. These construction materials may contain asbestos if they originate from buildings constructed before October 1993 – but in significantly lower concentrations than, for example, the well-known asbestos cement panels.

Multi-stage categorisation process

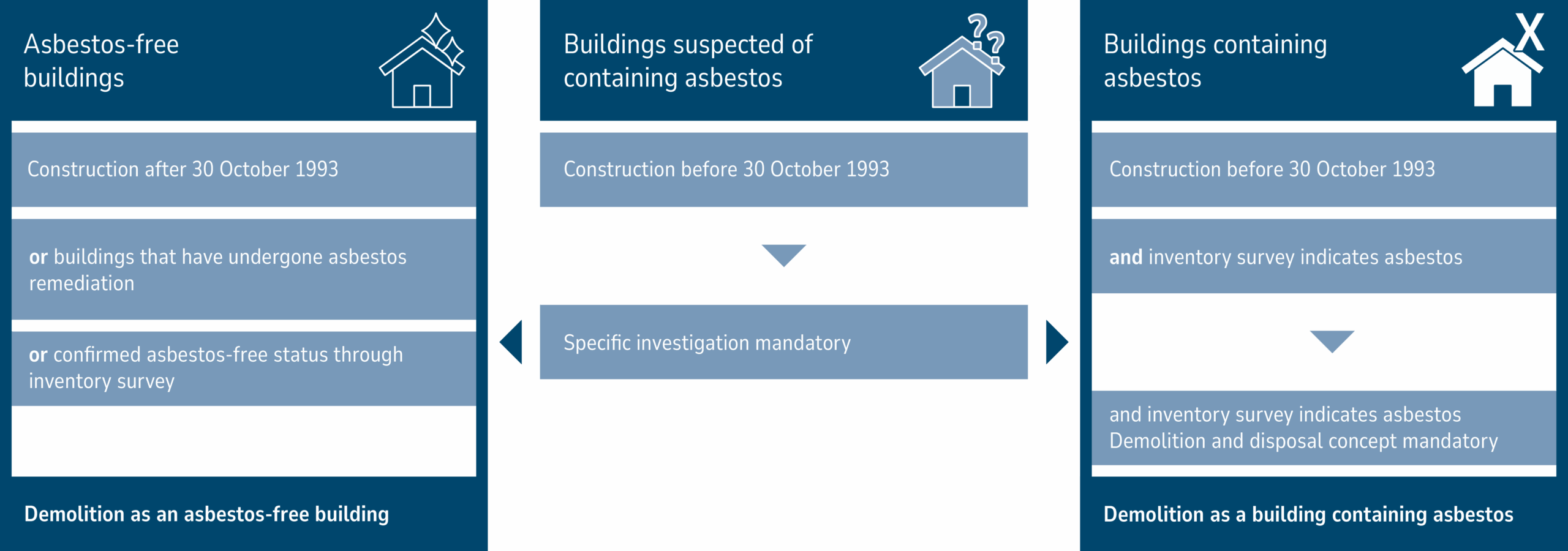

For buildings constructed before 31 October 1993, the new version of M23 therefore provides for a multi-stage procedure to determine the asbestos contamination of a building – including an obligation to investigate before the start of construction work, a demolition concept and DIN-standardised sampling of rubble. “The procedure is very costly for small, private construction and renovation projects. However, if there is no proof that the building rubble is free of asbestos, it is generally considered to be lightly contaminated with asbestos in such cases,” Kuhlmann quotes from M23. And that has consequences for the circular economy. “According to M23, we would no longer be allowed to recycle this construction waste; the material would have to be landfilled,” says legal advisor Kuhlmann.

Schematic representation of the dismantling principle of LAGA M23

Schematic representation of waste categorisation according to LAGA M23

Does LAGA M23 define a new type of waste?

Waste legislation only distinguishes between hazardous and non-hazardous waste. Some types of waste – known as ‘absolutely hazardous’ – are dangerous simply because they contain a pollutant (e.g. ‘insulation material containing asbestos’). The concentration of the pollutant is irrelevant in the case of this type of waste. For other hazardous waste – known as ‘mirror entries’ – asbestos must be taken into account as part of the general hazard characteristics. In the case of waste containing asbestos, waste is considered hazardous according to the Waste Catalogue Directive if the asbestos content is at least 0.1 per cent by mass. If it is below this, the waste is considered non-hazardous and should therefore be recycled to the highest possible standard. The LAGA M23, which is not legally binding, introduces its own threshold value of 0.01 per cent by mass of asbestos. Waste exceeding this value would have to be declared as ‘low-level asbestos-containing, non-hazardous waste’ and may no longer be recycled.

Material flow shift to landfill

From a material flow perspective, waste from private building renovations is of relatively little significance. “LAGA M23 is particularly important for the circular economy in the area of infrastructure renovation,” says Kuhlmann. According to the Federal Ministry of Transport, 8,000 motorway bridges in Germany alone need to be renovated – 4,000 of them within the next ten years [2]. Most of these dilapidated bridges will contain asbestos-containing spacers in reinforced concrete, which were commercially available in the past.

It is currently not technically possible to separate these small asbestos-containing parts from the rest of the construction waste to the extent required. According to the LAGA Working Group on Waste, the construction waste generated during bridge renovation would have to be declared as low-level asbestos-containing, non-hazardous waste and disposed of, i.e. sent to landfill. If LAGA M23 were to be implemented consistently, many millions of tonnes of recyclable concrete rubble would end up in landfills unnecessarily.

Landfilling without a waste code number?

In addition to this impending waste of resources, the question will be which landfills would accept this waste in the first place. This is because authorities issue waste code numbers to operators of waste treatment facilities to indicate which types of waste they are permitted to dispose of. The list of waste code numbers is regulated uniformly across Europe by the European Waste Catalogue, which is implemented in Germany by the Waste Catalogue Directive. “There is currently no such thing as non-hazardous waste that explicitly contains asbestos in European or German waste legislation,” says Kuhlmann. It is therefore questionable whether, for example, an operator of a Class I landfill site would accept waste containing asbestos, even if it is not considered hazardous. In addition to wasting resources and landfill capacity, the implementation of LAGA M23 would significantly increase legal uncertainty for all parties involved. The renovation of old housing stock will certainly become more expensive – as will the renewal of infrastructure that is in urgent need of renovation.

The updated LAGA M23 aims to minimise asbestos risks, but unnecessarily restricts the recycling of construction waste. This leads to more landfill, higher costs and a waste of resources – a more balanced approach is urgently needed.

[1] Schmidt, Christoph: Umgang mit Asbestabfällen: Bayern setzt statt der LAGA M23 auf FAQ-Katalog, erschienen am 18.07.2024 in EUWID Recycling und Entsorgung, online unter: https://www.euwid-recycling.de/news/politik/umgang-mit-asbestabfaellen-bayern-setzt-statt-der-laga-m23-auf-faq-katalog-180724/ (zuletzt gesehen am 15.9.2025).

[2] Bundesministerium für Verkehr: FAQ zur Brückenmodernisierung, online unter: https://www.bmv.de/SharedDocs/DE/Artikel/K/brueckenmodernisierung-faq.html (zuletzt gesehen am 15.9.2025).